From horse and buggy to genetic testing: How an Iowa woman's aortic condition led to much more

This article, shared with permission from Omaha World-Herald medical reporter Julie Anderson, details how cardiologist Angela Yetman, MD, has done extensive detective work to find nearly 100 family members with the same condition.

Rosana Taylor was standing in her kitchen one day about eight years ago when she suddenly felt like she’d been shot in the stomach. Everything felt like it was draining out of her.

After a few false starts, she was flown to the Nebraska Medical Center in Omaha, where doctors discovered a dissection or tear in the lining of the aorta — the big, blood-carrying artery — in her abdomen. After enough scar tissue formed, she had surgery to repair it.

About six years later, her oldest brother, who lives in another state, had emergency surgery to repair an aortic dissection in his chest, a life-threatening condition that often is deadly.

Around that time, Taylor, who is now 70 and goes by Rose, was referred to Dr. Angela Yetman, a cardiologist with Nebraska Medicine who specializes in diseases of the aorta and serves as medical director of its aortopathy clinic.

With signs pointing to a genetic cause, Yetman tested Taylor, her brother and other family members who’d experienced problems with their aortas. She determined that they shared a variant or mutation — one new to medical science — in a gene called SMAD3 that is involved in the integrity of the aorta’s muscle wall.

Yetman and her team since have tested 242 members of Taylor’s large, extended Mennonite and Amish family. Ninety-seven of them have the genetic variant.

“She knows my family better than I do,” Taylor said.

But as with plenty of other heritable conditions, finding the cause is just a first step. And the discovery itself serves as a reminder of the importance of knowing, exploring and acting on family medical history.

While there’s no cure for the condition in Taylor’s family, some effects can be managed and deaths can be averted, Yetman said. But that means those who have the variant need to know and be evaluated to determine whether they have aneurysms, or bulges in the wall of the vessel. Smaller ones, as well as some tears in the abdominal aorta, can be monitored and managed through tight blood pressure control. But aneurysms that reach a certain size require repair.

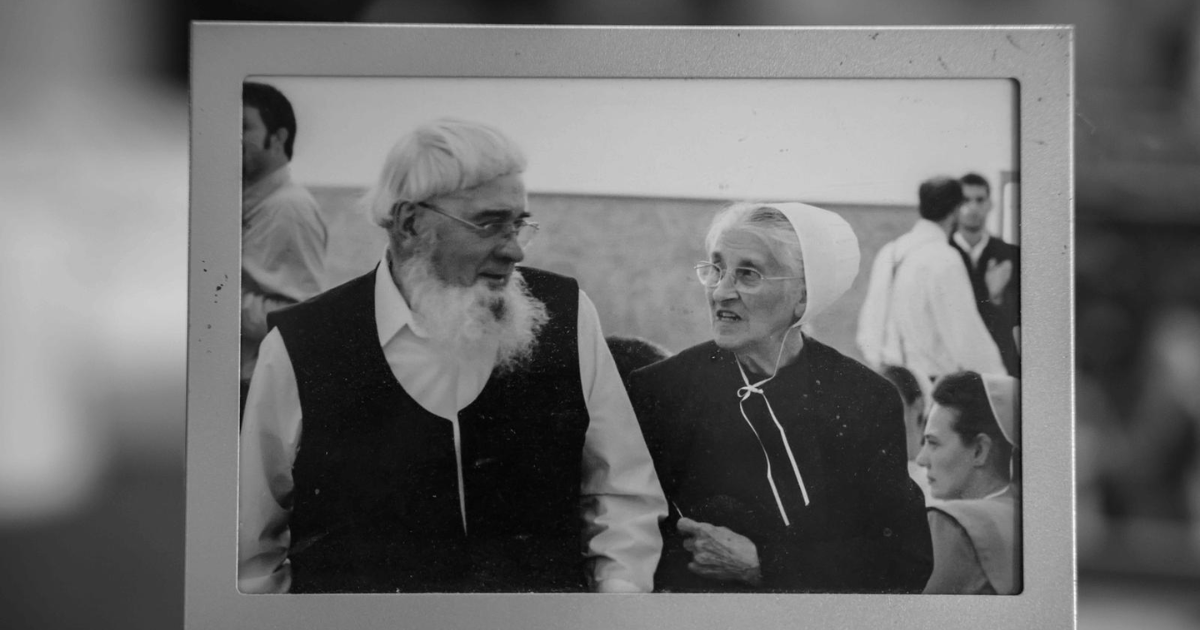

Connecting to family through house calls, letters and buggy

So last week, Yetman, who keeps Taylor’s family tree on a wall in her office, traveled to southeast Iowa to evaluate 18 family members who are among the 242 who have tested positive for the genetic variant. They’re part of an old order Amish community that Taylor’s parents, grandparents and other relatives helped found decades ago. Because of their beliefs, the family members don’t have health insurance, drive cars, keep telephones in their homes or use email or the Internet, Yetman said. That and their rural location make it difficult for them to access specialty care.

So Yetman paid some old-fashioned house calls. Her team performed echocardiograms and electrocardiograms on descendants of one of Taylor’s sisters — they’re among 10 siblings — who carries the variant. Its inheritance is dominant, so carriers have a 50% chance of passing it to a child. The work was funded by a grant from the University of Nebraska Medical Center and the Child Health Research Institute, a partnership between UNMC and Children’s Nebraska.

Yetman plans to return in a few weeks to evaluate 28 additional family members. The team eventually plans to visit another brother in southern Missouri who also is old order Amish. She previously has visited Taylor’s oldest brother, who suffered the dissection after Taylor did, and some of his family members. One of his sons also has had a repair, but another died suddenly in his early 40s, leaving a wife and two young children. No autopsy was performed to determine the cause of his death, however.

“The idea is to figure out who has an aneurysm and let people know before it tears, because that’s what’s lifesaving,” Yetman said. “It doesn’t do you any good to know you have a gene if you don’t know you have an aneurysm and aren’t having it followed.”

The team didn’t find any issues that require immediate action during its initial trip to Iowa. But they previously found two family members who had aneurysms of a size that required surgery. Both have had successful procedures, Yetman said, all thanks to Taylor.

“This really allows us to work with the families to get them the answers they need to keep everybody safe, but at the same time they’re contributing to science,” she said. “It’s a wonderful blend of the medical community and the community coming together.”

Tracing the variant and connecting with family members scattered across a half-dozen states and of varying levels of worldliness, however, in some cases took some old-fashioned detective work.

Taylor, who moved to Red Oak with her late husband in 1989, called some initially. Yetman emailed some; Taylor uses a cellphone and other modern technologies but hasn’t mastered that one. Yetman also wrote a letter explaining the condition, which Taylor sent to her sister in the Iowa Amish community to distribute to others. One family member also helped Yetman post information in a family letter that’s distributed by fax.

During their Iowa visit, the team initially set up at the home of one family member. Another family traveled there by horse and buggy. To reduce their travel time, the team then opted to drive to others’ homes.

Yetman said she felt honored to be able to make the house calls, and family members were very grateful. At one point, they provided a lunch feast with three kinds of pie. They sent the team home with fresh produce, huge chrysanthemum plants and “the biggest watermelon you’ve ever seen.”

'That's why God saved my life'

Taylor said it was a “pretty heavy load” when her first nephew had surgery. She worried he might not survive and wondered whether she had done the right thing by alerting her family. But he came through fine.

“I feel like maybe that’s why God saved my life, is because we did need to know,” she said. “He spared me so I could, (and) then, luckily, led me to Dr. Yetman.”

Yetman said researchers are learning more and more about the importance of genes when it comes to aneurysms. Both the American College of Cardiology and the American Heart Association recommend that anyone under 60 who has an aneurysm be screened for a genetic component.

And in families with a history of an aneurysm in someone under 60, all first-degree relatives — parents, siblings and children — should be evaluated.

Taylor’s grandfather lived into his 90s but had had aortic surgery. He had 12 children, one of whom was Taylor’s father. He and three of his siblings carried the gene variant.

While researchers don’t always find genetic link, Yetman said, the number of variants they can screen for is much larger than it was even five or 10 years ago.

In testing Taylor’s family and going back through six generations of their family tree, in fact, the researchers also stumbled on another previously undiscovered variant in the same gene. It’s different than the one Taylor has but also is related to aneurysms. It originated in another family that married into Taylor’s clan.

Technically, the condition is one of a number of hereditary aortic aneurysm syndromes. The best known is Marfan syndrome, which has an incidence of about one in every 5,000 people. That’s about the same as the lung disease cystic fibrosis, Yetman said, but fewer people have heard of it.

But it’s important to distinguish between Marfan and the look-alike that runs in Taylor’s family, she said, because they behave differently. The size of the aorta where repairs are made also differs.

In fact, the SMAD3 gene that is altered in some of Taylor’s family members was only described within the past decade. Scientists still are learning about it, she said, asking questions such as the age at which carriers develop aneurysms and when they experience tears.

“That’s what I’m trying to work through with the help of this family,” Yetman said.

Taylor said tracking the variant through the family was an almost overwhelming task. But she and her siblings credit Yetman with getting the ball rolling.

“That’s just above and beyond,” she said, “and we’re so pleased that we found her, because she’s the one who actually decided there was more to it than just a few of us having aneurysms.”