'We're tired of watching people die': the 6 stages of critical COVID-19 care

This is what I'm seeing in my COVID-19 patients, depending on the amount of oxygen assistance they need. Every patient is variable, but it's typically a stepwise progression through these stages.

Emergency room triage

Most commonly, people come in with shortness of breath. There are usually other COVID-19 symptoms, like fever or fatigue, sometimes a cough. They're usually fairly hypoxic, which means they have low levels of oxygen in their blood. By this point, they've been battling COVID-19 for at least several days.

For a normal, healthy person, a blood oxygen reading is 90% to 100%. We've seen people in the emergency room in the 60% to 70% range because of COVID-19.

Admitted to the COVID-19 floor

We'll start you with a less invasive procedure to help you breathe, like a simple nasal cannula. This is a small, flexible tube that delivers air directly into your nostrils. Some patients only need 1 to 10 liters per minute of supplemental oxygen.

But others we have to put on “high flow” oxygen system – 30 liters to 70 liters per minute. That's a lot. It can be very uncomfortable as air will be blown up your nose at a very rapid rate. Your nose and mouth can become dried out, creating more discomfort. Eventually, the simple everyday activities that you do including eating, drinking, sitting up and even using the bathroom can become too difficult to do on your own.

More invasive procedures

Commonly, when I'm called in as an ICU physician, people are failing these less invasive or less aggressive forms of oxygen therapy. A BiPAP or CPAP mask to help you breathe is our next option. These masks will cover your entire nose and mouth, kept secure with velcro wraps around your head.

When a COVID-19 patient needs to be admitted to critical care, it's often a fatigue problem. You're breathing 40 or even 50 times every minute. If you think about that, it's almost one breath every second. That's on 100% oxygen, not on room air.

It's too hard for you to keep your oxygen numbers up. Small movements leave you gasping for air. You look exhausted and you can't maintain a breathing pattern on your own. Patients tell us it feels like they're drowning.

Getting intubated

If you're tired and not able to maintain enough oxygen levels even with 100% oxygen, we need to consider a more invasive procedure. Our last resort is mechanical ventilation through intubation. That means placing a tube in your windpipe to help move air in and out of your lungs.

It can be risky just getting you on the ventilator. Because you need mechanical assistance, you don't have great respiratory function at baseline. The minute you stop getting oxygen, your levels can dramatically crash. I've seen people go from 100% oxygen saturation to 20% or 15% in a matter of seconds because they have no reserve and their lungs are so diseased and damaged. When your oxygen level is that low, your heart can stop.

This is not something we decide lightly. But sometimes it's unavoidable and there's no other option. It might be the last time you have to talk to loved ones, so we make sure to let your family say their goodbyes, just in case we can't rescue you from this virus.

On the ventilator

Your risk of death is usually 50/50 after you're intubated. When we place a breathing tube into someone with COVID pneumonia, it might be the last time they're awake. To keep the patient alive and hopefully give them a chance to recover, we have to try it.

Normally, we breathe by negative pressure inside the chest. As we inhale, the muscles of our rib cage expand out and our diaphragm descends down, which produces negative pressure inside our chest. This allows air to enter our body in a gentle, passive fashion.

A ventilator is the exact opposite – it uses positive pressure. Critical care COVID-19 patients often have diseased and damaged lungs, to the point of scarred lung tissue. The positive pressure we use to push air into the lungs can be damaging to these weak lungs.

Sometimes, it takes high levels of positive pressure to allow adequate delivery of oxygen. This can cause a pneumothorax, a condition where air is outside of the lungs but still inside their chests. In order to avoid complications from a pneumothorax, we need to insert a tube into your chest to evacuate the air. If this air isn't evacuated, it can cause a tension pneumothorax which can be fatal. All of these issues add up and cause further lung damage, lessening your chances of survival.

If your lungs do not recover while on mechanical ventilation, we likely cannot do anything further to help. In these situations, we discuss withdrawing care from patients with their loved ones. It is a part of our job we hate. We don't want to stop, but there comes a point that we are no longer doing things to help you but are only causing more prolongation of suffering. Dying from COVID-19 is a slow and painful process. You literally suffocate to death. Many times, COVID-19 patients pass away with their nurse in the room. No family, no friends.

Extubation, followed by a long road of therapy

Hopefully, we can fix you and get you off the ventilator. Like I mentioned earlier, survival after intubation has the same odds of a coin flip. Extubation is a good thing because it means you survived the ventilator, but your battle is far from over.

Many times intubation requires a medically induced coma, meaning you're deeply sedated, similar to being under general anesthesia for surgery. Despite deep sedation, some patients still don't tolerate mechanical ventilation due to excessive coughing, or dysynchrony with the ventilator. Sometimes, we need to chemically paralyze you in order to completely take over function of your body. This allows us to make certain that you are able to achieve optimal support from the ventilator. Some COVID patients require days, if not weeks of sedation and paralysis.

After a long run on a ventilator, many patients are profoundly weak. This is a consequence of the long term sedation and paralysis that many patients require in order to recover from COVID-19. Like anything else in the body, if you don't use it, you lose it. Patients lose up to 40% of their muscle mass after being intubated for 20 days. This leads to many issues after extubation that will require weeks of rehabilitation and recovery. In some circumstances, patients are so weak that they require placement of a tracheostomy to allow slow weaning from the ventilator. A tracheostomy is a surgically inserted airway device directly into your windpipe in your neck.

You can have a hard time walking, talking and eating after you are extubated. It's the norm to have a feeding tube in your nose because your swallowing mechanics are so weak and abnormal that you can't swallow anymore. Many folks are aggravated and frustrated because they can't enjoy a glass of water, or their favorite foods. It can take weeks to gain that function back again.

You have to relearn a lot of things you probably took for granted when you were healthy. You require aggressive rehab in either a skilled nursing facility or an acute rehabilitation program. This will take months. I tell my patients' families that for every day they lay in an ICU bed, plan on a minimum week of rehab. So if you're paralyzed and intubated for three weeks, that's a minimum of 21 weeks of rehab.

We're having trouble discharging people from the hospital into rehab because all of the rehab facilities are full.

We're tired of watching people die from a preventable disease

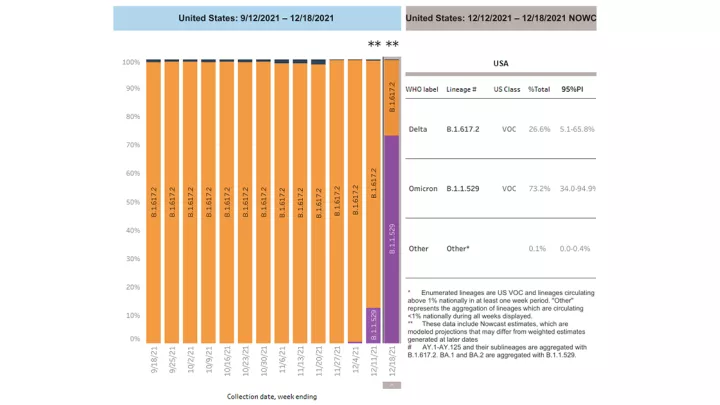

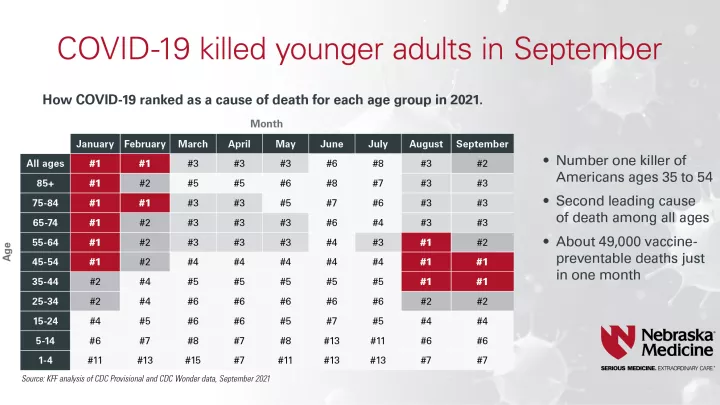

The delta surge feels different from the surge last winter. Patients get sicker faster. They go from OK to not OK in a matter of hours, and in extreme cases minutes. I had one patient who looked fine in the morning, and by lunchtime I had to put a breathing tube in, and by dinner time, we were doing CPR.

They're younger, too. The last time I was in the COVID-19 ICU, I don't think I had one patient over the age of 60.

It's been said over and over again, but it's profoundly true. We're sick of this. Just like everyone else, we don't like wearing masks all the time or limiting what events we can go to or the people we can see. We're tired of the pandemic, too. If there's a huge influx of hospitalizations because of omicron, I don't know what we'll do. We have nowhere to put these people. The hospital is full and we're tired.

We're tired of seeing our patients struggling to breathe.

We're tired of people dying from a preventable disease.

We're tired of watching young folks die alone.

We're tired of family members being aggressive with care providers because we're not giving the drugs the internet or the news told them were better. When all those things have not been proven to be helpful whatsoever.

The fatigue is very real. I honestly don't know what the health care world is going to look like when this is all said and done. Especially when now there are tools and evidence and things you can do to prevent it. If you're vaccinated you can still get COVID-19, obviously, but you're much less likely to get so sick that you'll go to the hospital and you're much less likely to die.

We're tired of COVID-19, just like everyone else is. But everyone else doesn't have to watch people suffer and die on a daily basis.